Symmetrical geometries in saturated purples, reds, magentas, and blues contrast with washed-out pastels – negative spaces of sorts. The imperfect edges of the triangles, trapezoids, diamonds, and parallelograms; the diagonal, vertical, and horizontal axes, blur – but never entirely – into, onto, and over each other in a soft play of gradations and shadows. Viewed from just a short distance, the shapes shimmer, flicker. Berlin-based artist Anja Schwörer’s textile works are multidimensional, but also somehow transcendental, studies in shape, color, and materiality.

Each work begins with fabric stretched on a conventional wood frame, the underlayer of densely woven fabric appearing in stark blocks of bright colors. Stretched over the color blocks is a second layer of cotton mesh manipulated by the artist – at times loosely woven in a visible grid, at times denser, less porous – which has been imbued with its variegated colors scheme in rich dyes, bleach, or both. The layers are made separately, the first sewn together, the second a single piece that has been folded, dyed, and bleached in varied steps that result in the gradations of color, but also the mirroring, symmetries, and kaleidoscopic effects of the whole. The two layers’ color combinations are both calculated and left slightly to chance.

In many cultures, folding can be a ritualistic, meditative, or even a performative gesture – consider shibori, the Japanese art of folding fabric in preparation for resist dying, creating repetitive patterns in the cloth surface; a technique the artist has studied. To the artist, fabric, too, is more object than blank surface. “Making these works is an almost sculptural process,” says the artist in her studio, several ground-floor rooms in soflty diffused light in a northern Berlin district. In some rooms dye baths dot the floor; in others, fabrics hang to dry on clotheslines; folded fabrics that Schwörer acquires in her travels lie in stacks. One room is filled with finished stretched works hanging on or stacked against walls. Pieces from a current work series combine and juxtapose hues associated with vibrance and high energy; red, purple, blue – the shades that denote higher levels of conciousness and being in both western color theory and eastern philosophical thought.

Schwörer uses additive techniques (dyeing), but also substractive one (bleaching). Each fabric weave and each new color combination become a new journey in experimentation: Beyond the loose cotton mesh, she has worked with denim and fine-weave poplin. The artists aims to create an individual aura with each piece, and one recalls artist/textile designer Anni Albers, whose repetitive, geometry-infused textile designs created more than a century ago blurred the lines between fine and applied art, but also, perhaps, the more overtly spiritual, otherwordly inclinations behind the subtly powerful lines and grids of painter Agnes Martin or the vibrant abstract colors and shapes of Hilma af Klint.

Decades later, Schwörer links to – but also rises above – notions of mere applied art. The auras that each of Schwörer’s works ultimately emits pack an earthier, headier punch than those of Martin. Beyond its materiality, this is art that is about mapping a path, but also allowing or encouraging deviations along the way. Its is about exploring the powers of form, color, and chance, all of which interlock and intertwine into something greater than the sum of their parts. It is, too, perhaps about connecting to so many predecessors – from the aforementioned artists but conceptually reaching back to the ancients – who were drawn to ritual and repetition reaching for a higher order and meaning.

text: Kimberley Bradley, 2021

CLARA BRÖRMANN, CAROLINE KRYZECKI, HALEH REDJAIAN, ANJA SCHWÖRER

Exhibition: 22 January – 27 February 2021

SCHWARZ CONTEMPORARY

Text: Lena Fließbach

Translation: Wilhelm Werthern

Anja Schwörer’s works are not the result of adding paint to a canvas; rather, the textile material on a stretcher frame is stripped of colour. The artist explores how industrially manufactured fabrics such as denim, velvet, or polyester react to textile techniques like bleaching or tie-dyeing. Taking geometric figures – the circle, the rectangle, or the line – as points of departure, she also refers to the grids and basic forms which are the foundation of the structure of textiles and the mechanics of the loom. The geometric figures, whose edges always are blurred in Anja Schwörer’s work, point to the individual steps of their genesis, i.e. folding, knotting, or tying. Many works are dyed by hand and inspired by the Japanese Shibori technique. Both the texture and the plasticity of the fabric are emphasized through this method. The artist’s work process is determined by the unpredictable reactions of the material, which reacts to the poured, dunked, or sprayed bleach according to its own rules depending on its weave, elasticity, and colour. Sometimes, the borders of the bleach poured on the support are blurry or cloud-like, sometimes the folding process on a mesh fabric leads to a superimposition or shifting of diamond or rectangular shapes.

Text: Ursula Ströbele

Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens, Cologne 2013

Anja Schwörer – To Hell and Back

Das in regelmäßigen Abständen erneut proklamierte Untergangsszenario vom Ende der Malerei führt bekanntlicherweise weniger zu einer Abkehr von diesem scheinbar anachronistischen Medium als vielmehr zur Aufhebung des Nullpunkts zugunsten erweiterter Blickwinkel auf die üblichen gattungsspezifischen Parameter.

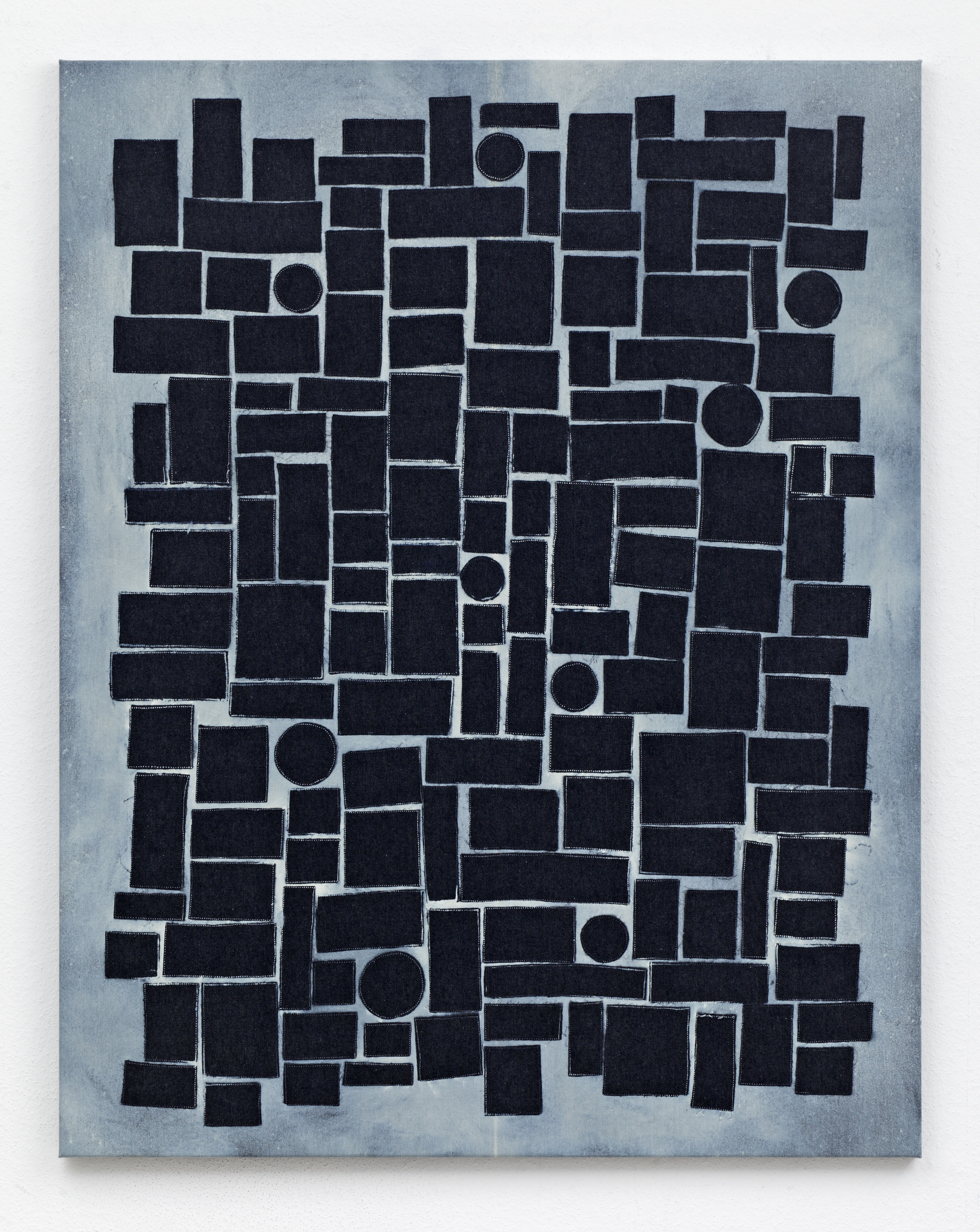

So lassen sich auch die in der Galerie Hammelehle und Ahrens präsentierten Arbeiten Anja Schwörers aus der Intention heraus verstehen, den ikonoklastischen Paradigmen demonstrativ zu begegnen und die totgeglaubte Malerei zu neuem Leben zu erwecken. „To Hell and Back“ lautet der Titel ihrer vierten Einzelausstellung in Köln, die eine Auswahl jüngst entstandener Bilder vereint und auf den Song einer englischen Black Metal-Band rekurriert. Das hier implizite Bewegungsmoment im Sinne eines Hin und wieder Zurück, einer ´Neuschöpfung´ vergleichbar Phönix´ Geburt aus der Asche mündet in eine ikonographische und materialästhetische Herangehensweise, die mit dem klassischen Kanon bricht und andere Techniken integriert. Anstelle des additiven Farbauftrags greift die Künstlerin auf industriell gefertigte Textilien, größtenteils Jeansstoffe in verschiedenen Tönen und Waschungen – wie sie den Modetrend der letzten Jahre vornehmlich prägten – zurück, die sie anschließend einem komplexen Bleichprozess unterwirft. Abhängig davon, ob die Bleiche gesprüht oder geschüttet, die Baumwolle gefaltet, geknotet oder partiell bedeckt wird, entsteht ein abstraktes Allover-Pattern mit feinen Farbverläufen, die ihrerseits als Spur auf die einzelnen Schritte der Entstehung deuten. Im Unterschied zu ihren früheren, teils mit geometrischen Liniengebilden überzogenen Batikarbeiten verwendet Schwörer in den „Brick- und Flicken-Bildern“ Reststoffe aus dem eigenen Atelierfundus, die entweder unbehandelt sind oder gestische Schlieren bzw. Kleckse älterer Bemalungen aufweisen. Ähnlich der auch aus der Hippiebewegung bekannten Patchwork-Technik sind einzelne Stoffteile zu einer Fläche zusammengenäht und auf einen Keilrahmen gespannt. Doch anders als beim traditionellen Tafelbild variiert die Tiefe des Trägers zugunsten einer stärkeren Betonung des Objektcharakters. Während bei den pastellfarbigen „Flicken-Bildern“ die unregelmäßige Größe der Rechtecke und das Hervortreten der hellen Fäden eine besondere Dynamik und Zeitlichkeit evozieren, formulieren die in ihrer streng geometrischen Form an Mauerziegel erinnernden „Brick-Bilder“, deren Nähte unsichtbar bleiben, eher eine statische Präsenz. Die einzelnen Textilfragmente folgen keiner bildinhärenten Logik oder Symmetrie. Ihre minimal-serielle, horizontale Aneinanderreihung und das nicht eindeutig vorhersehbare Eigenverhalten des jeweiligen Gewebes während der Bleiche relativieren die Dominanz einer persönlichen Handschrift und knüpfen an die seit der Minimal Art postulierte Reduktion von Autorschaft an.

Eine Variante der Patchwork-Technik ist die Applikation, d.h. einzelne Teile werden aufeinander gelegt und fixiert. Bekanntheit erlangte diese Verwendung von Aufnähern innerhalb der Jugend- und Subkultur als Zeichen eines favorisierten Musikstils, u.a. Heavy Metal, und Ausdruck von Gruppenzugehörigkeit – Erinnerungsfetzen an eine vergangene Zeit mit eigenen Utopiegedanken. In Anja Schwörer´s Arbeiten bleiben die Patches selbst aber verborgen und lassen nur durch die auf dem Bildträger markanten dunklen Färbungen und durch die teils sichtbaren weißen Nadellöcher wie umrisshafte Schatten ihre ursprüngliche Anwesenheit erahnen. Sie füllen die Fläche zu einem labyrinthartigen Grid und öffnen sich selbst dank ihrer monochromen Farbigkeit und geometrisch reduzierter Kontur individuellen Sehnsüchten und Projektionen – das suchende Auge schweift auf der Oberfläche hin- und her.

Charakteristisch für die experimentelle Herangehensweise der Künstlerin an den kontrovers geführten Diskurs der Malerei in der Nachfolge der von Rosalind Krauss formulierten „post-medium condition“[1] ist neben der inversiven, subtraktiven Praktik auch die partielle Zerstörung des Bildträgers selbst. Kalligraphisch anmutende Ritzungen auf der Oberfläche holen ein subjektives Moment in die Komposition zurück, an den Rändern ausgefranste Löcher und Einschnitte erlauben Durchblicke ins Ungewisse. Das Kaleidoskop der Malerei birgt noch unbekannte, zu entdeckende Facetten, denen Anja Schwörer sich in einer vielversprechenden, spannungsreichen Sprache annähert, um neue Wege zu öffnen.

[1] Vgl. Rosalind Krauss, A Voyage on the North Sea. Art in the Age of the Post-Medium Condition, London 2000.

Anja Schwörer

By Bob Nickas

Page 92 in Bob Nickas: Painting Abstraction: New Elements in Abstract Painting - The definitive guide to contemporary abstract painting. Phaidon 2009.

Titles, for abstraction in particular, can open up pathways into artworks, into their sources and meanings, can direct our readings in ways we might not have otherwise considered, and can even offer insights to the mind of the artist. A title may also lead nowhere useful, or even to misdirection, which mayor may not be the artist's intention. A title can be thought of as either an anchor holding an object, still buoyant, in place, or as so much dead weight. Anja Schwörer, for her part, never titles paintings. The works are already so visually suggestive - of the cosmos and infinity, of order and disorder, of what is knowable and unknowable, of the heavens and darker realms - that language would only interfere with their energy and resonance. Her works are in no way mute; they are in fact the results of visible transmutation, and for the viewer there is a kind of unspoken agreement: to look at the work is to cede to them, if only momentarily, as objects of contemplation, evoking either wonder or dread. Schwörer has said that she is interested in where abstract art comes from, and a number of artists are brought to mind - Kandinsky, Noland, and Stella - but she also has an affinity for spiritual and esoteric pursuits (one can't help but think of William Blake and "the doors of perception" in this respect), to which she remarks, "I am making ornaments to express the indescribable."

Schwörer’s works are characterized by various dualities; on the one hand there is control, as created by geometric elements (geometry, that perfect world), and on the other there is a great degree of chance in her initial procedures (chance, the aleatory world). She is always interested in the realization of the works being poised between certain and uncertain outcomes. Untitled (2008), for example, was made by first stretching black fabric covered in wax, using a knife to incise lines in the wax, bunching up the fabric from the center outward and tying it with string, pouring bleach, then opening it up and painting the spiral. The resulting picture, complete with the signs of its making, appears to be a chaotic, exploding world with an unbroken but unraveling timeline. With the batik process, Schwörer refers to the bleaching as an act of deletion, a further dualism in her work, between

what is given and what is taken away. Removal, however, is almost always followed by a further layer, the geometric structure or ornamental "grille" that sits on the very surface of the picture plane. The Iron Cross-like form that dominates Untitled (2008) acts as a barrier before a blackened sky, while the harlequin-patterned screen in Untitled (2007) offers myriad diamonds framing a view of a smudged twilight. The iconic white mirrored form central to Untitled (2008) is like a geometric spider that spreads across a well or chasm into which we look vertiginously down. The grille, which Schwörer sees as "a kind of force field" or portal, is always symmetrical, an image of reflection and doubling.

A recent work, a red and black Rorschach folding in and out of itself, bleached on velvet, merges its symmetry with the very process by which it was created, a further dualism: between handcraft and geometry, between earthly and higher planes.

Near mystical, Blakean visions of deep space in a number of black paintings from 2007 reveal Schwörer’s darker sensibility (as well as her interest in metal bands like Bolt Thrower, High on Fire, and EyeHate-God). These are among her most stunning and enigmatic works to date. In one, an intensely bright white light with radiant beams holds the center of a deadened universe, while in another a "black sun" is the vortex of an eerily silent field of what might be gas, dust, and stars - a sublime spiral galaxy. Schwörer’s painted/dyed works correspond to another area of activity: her production of photograms, pictures made in the darkroom without a camera. For these she chooses vernacular objects - a wind chime, for example and engages with the tradition of working with light to create an image. She relates them to her studio practice, noting, by way of reversal, "in the paintings I delete light' Whether considering the painted/dyed/ bleached works or Schwörer’s photograms, it's the alchemical nature of her endeavor that unifies this parallel universe.